When you become interested in the art of tea ceremony, you might naturally want to learn about how it originated and evolved to its present state. As tea ceremony is strongly associated with the image of Sen no Rikyū, many people tend to imagine that he was the one who initiated tea ceremony.

Certainly, Sen no Rikyū made significant contributions to the establishment of the tea ceremony (wabi-cha) as we know it today. However, tea ceremony was not started by Rikyū alone, nor is his particular form the only one that has persisted through the ages. Let’s delve into the deep history of tea ceremony.

What is Sado?

Firstly, what is “tea ceremony”? From the words themselves, it might refer to a path of mastering the method of savoring tea. However, what we associate with the term today is the way of tea involving rituals and spirituality. This concept of tea ceremony appears in literature related to tea from the late Azuchi-Momoyama period to the early Edo period.

Furthermore, Okakura Kakuzō mentions in his book “The Book of Tea” that it was in the 15th century when the enjoyment of tea transformed into what could be called a “way of tea.” He explains that around the late 15th century (late Muromachi period), tea began to be pursued with a certain spiritual essence and accompanied by specific rituals, which is essentially what we refer to as “wabi-cha” today.

Tracing the History of Tea

■ Origins of Tea Consumption

The origin of tea plants is believed to be in regions like Assam in India, Yunnan Province, and Sichuan Province in China. Chinese records from around the 1st century BC and after mention tea, suggesting that it was already being consumed during that time. Subsequently, tea gained popularity during the Tang Dynasty, and a scholar named Lu Yu wrote the world’s first tea book, the “Classic of Tea.” The way of consuming tea during this period involved placing tea powder into boiling water in a kettle, then ladling it into a bowl for drinking.

■ Early Tea Consumption in Japan

Evidence of early tea consumption in Japan can be seen in temple events during the reign of Emperor Shōmu. Records mention the consumption of tea with ingredients like amadzura (sweet flag) or ginger. In the Heian period, there are numerous mentions of tea in relation to Emperor Saga, indicating his fondness for tea. It’s believed that during this time, tea was prepared by grinding tea leaves into a ball-like shape and steeping them in water, known as “dancha.”

■ Eisai’s Promotion of the “Matcha Method”

Eisai, who became the founder of the Rinzai Zen sect, is said to have introduced the practice of whisking powdered tea into hot water to create matcha.

During the Kamakura period, when the consumption of matcha became popular in Japan, there is a record that Eisai gave it to Minamoto no Sanetomo, the third shogun of the Kamakura shogunate, as a medicinal drink. Eisai is known for writing the first tea-related book in Japan, called the “Kissa Yōjōki” (A Prescription for Drinking Tea for Health), where he discusses tea as a longevity elixir. Interestingly, it’s now believed that the discomfort Sanetomo experienced after drinking tea from Eisai wasn’t an illness but rather a hangover.

■ Popularity Among the Warrior Class

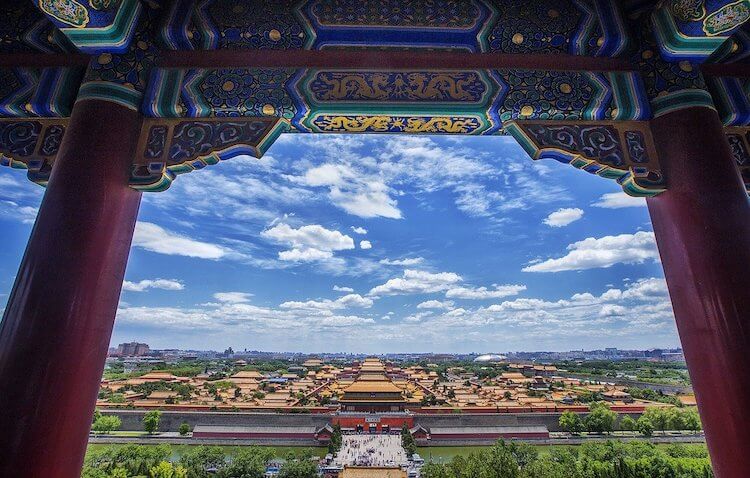

During the Muromachi period, samurai imported vessels from China, using them as tea bowls, tea caddies, and flower vases, and displayed them in private spaces known as “kaisho” within their residences to enjoy tea. These vessels imported from China are referred to as “karamono.” It’s important to note that “karamono” doesn’t strictly refer to items from the Tang Dynasty; it includes items from the Song, Yuan, and Ming Dynasties as well.

The Ashikaga shogunate also collected Chinese wares through trade with Ming China, spanning from the third shogun, Yoshimitsu, to the eighth shogun, Yoshimasa. These pieces eventually scattered into the city due to the shogunate’s decline. However, those collected by Yoshimasa at the Eastern Mountain Palace, which he constructed for his retirement, became known as the “Higashiyama Gomotsu” or “Eastern Mountain Treasures.”

↓ Below is one of the collected art pieces, an Important Cultural Property known as the “Taihi San Ran Temmoku” (Bowl with Brown Glaze and Temmoku Glaze)

Additionally, a game called “Tōcha” (Tea Battle) became popular, where people would taste and compare different matcha from various regions to guess their origins. Kyoto’s Toganoo tea was considered “honcha” (main tea), while teas from other regions were labeled “hicha” (non-main tea). This game gained popularity not only among samurai and nobles but also among some affluent commoners. Prizes such as Tang Dynasty tea utensils, swords, and even gold nuggets were sometimes awarded.

Origin of Wabi-Cha in Tea Ceremony

■ Believed to have started Wabi-Cha – Shukō –

The person often credited with initiating the style of tea that emphasizes spirituality, known as wabi-cha, which connects to modern tea ceremony, is Shukō (also known as Murata Shukō). There are few historical records about Shukō, and many aspects of their life remain unknown. However, they believed that a spirit of “cool austerity” was essential in tea, and they advocated for using not only imported Tang Dynasty tea utensils but also Japanese-made tea utensils, integrating them into a unified way of tea.

Rather than adorning showy Tang Dynasty tea utensils, they favored tea utensils with a simple and unpretentious appearance. One of Shukō’s famous sayings is “Tsuki mo kumoma no naki wa iya nite sōrō” (I don’t like the moonless sky without a single cloud). This saying captures Shukō’s spirit of finding beauty in the simple and imperfect.

Further Development of Wabi-Cha – Takeno Shōō –

Advancing Shukō’s wabi-cha approach further was Takeno Jōō (also known as Takeno Shijō), who transformed from a merchant in Sakai into a tea practitioner. Although Jōō was born around the time of Shukō’s passing, they didn’t have a formal student-teacher relationship. Nonetheless, Jōō admired the spiritual essence of wabi-cha that Shukō began.

While cherishing elegant and venerable Tang Dynasty tea utensils, Jōō also introduced new tea utensils like “shōō fukurodana” (shōō bag shelf) and bamboo lids. Jōō’s style of tea ceremony was passed down to disciples like Sen no Rikyū, and as a result, Jōō can be regarded as a significant figure in the establishment of the tea ceremony.

The Emergence of Sen no Rikyū

Sen no Rikyū, who originated from Sakai as a merchant, studied under Takeno Shōō and learned the principles of wabi-cha. He served as a tea master under Oda Nobunaga when he traveled to Kyoto, and after Nobunaga’s passing, he became the tea master of Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Originally known as Sen Sōeki, the name Rikyū is a layman’s title, signifying a name within the Buddhist community.

Rikyū further embraced the spirit of “wabi” in tea ceremony and pursued an even simpler and more minimalist approach. While most tea rooms at the time were around four and a half tatami mats in size, Rikyū designed a two-tatami mat tea room. Beyond size, he introduced innovative features such as a low entranceway (nirijiguchi) to enter the tea room by crouching down and walls plastered with earth in the corners (murotoko), making one’s body smaller to fit. He also began using new utensils such as bamboo tea scoops and black Raku tea bowls crafted by Chōjirō.

All these changes embraced a minimalistic aesthetic by removing unnecessary decorations. The tea rooms and tea utensils devised by Rikyū are considered symbolic of the spirit of tea ceremony and continue to influence modern tea practices.

While Takeno Shōō is often credited with establishing the foundations of tea ceremony and wabi-cha, Rikyū is recognized for bringing these principles to their pinnacle and achieving their full realization.

Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi in the World of Tea Ceremony

■Nobunaga and the Tea Ceremony

Whether drawn to the world of tea ceremony by genuine interest or using it as a strategic tool for his ambitions of unification, Oda Nobunaga effectively utilized tea ceremony for political purposes. During his time in Kyoto with Ashikaga Yoshiaki, he engaged in a practice known as “Meibutsu Gari,” where he forcibly acquired renowned tea utensils from the Kinki region he had subdued. These utensils were used in tea gatherings to not only showcase Nobunaga’s power but also to reinforce dominance over his guests and strengthen the hierarchical relationships between himself and those he entertained.

Nobunaga also rewarded accomplished samurai with famous tea utensils and required his permission for conducting tea gatherings, all of which reflects the political use of tea ceremony.

Furthermore, he employed skilled merchants from Sakai who were well-versed in the ways of tea. Among them, Imai Sōkyū, Tsuda Sōkyū, and Sen Sōeki (later known as Sen no Rikyū) would later be collectively referred to as the “Three Grand Tea Masters of the World.”

■Hideyoshi and the Tea Ceremony

After the Incident at Honnō-ji and the Battle of Yamazaki, Hideyoshi, who succeeded Nobunaga, hosted significant tea gatherings that left a mark in history. These gatherings, which included many participants, were held at Daitoku-ji Daichawarayu, an event at the Imperial Palace attended by the Emperor and nobles, known as the Kinchū Chakai, and the grand tea ceremony at Kitano Shrine with a golden teahouse. These events were believed to serve the purpose of showcasing Hideyoshi’s power, authority, and wealth as the ruler.

The relationship between Hideyoshi and Sen no Rikyū is also well-known. Rikyū not only managed the logistics of tea gatherings as a “Tea Master,” but he also established his position within the political sphere. Although Hideyoshi later ordered Rikyū to commit seppuku, the reasons behind this decision remain subject to various theories.

The Establishment of Tea Schools Leading to the Present Day

■Early Edo Period

As the Edo period began, individuals who had learned tea ceremony under Sen no Rikyū, and their disciples, started adding their personal touches to tea ceremony practices. Among them were Furuta Oribe, Hosokawa Sansai, Gamō Ujisato, and Kobori Enshū, individuals who held power and authority as samurai. This era witnessed the birth of numerous schools that continue to influence tea ceremony practice today.

In the Sen family, which traces its origins back to Sen no Rikyū, his grandson Sōtan dispatched his three sons to prestigious daimyō families. These three sons established their own schools: Omotesenke under the third son Sōsa, Urasenke under the fourth son Sōshi, and Mushakōjisenke under the second son Sōshū. These three families are known as the “Three Sen Schools” and have continued to pass on Rikyū’s tea ceremony.

■Mid to Late Edo Period

During the middle and late Edo period, tea ceremony continued to spread. Affluent merchants gained prominence, and tea ceremony became popular among them, extending its influence beyond the samurai class. The practice matured during this period, with new procedures established by different schools, and many books written about the philosophy and utensils of tea ceremony. The “Chaji,” tea gatherings with a set structure, also emerged during this time, with the Chajin specializing in the creation of tea utensils.

In the late Edo period, Ii Naosuke, most known for the Ansei Purge, stands out as an interesting figure. Despite his controversial history, he was highly regarded as a tea practitioner and authored “Chanoyu Iketsu Shu” among other tea-related writings. This work delves into the spiritual aspects of tea ceremony, emphasizing concepts such as “Ichi-go Ichi-e” (treasuring the moment) and “Dokusaza Kinen” (appreciating solitude).

Modern Developments in Tea Ceremony

With the advent of the Meiji period, tea ceremony lost the support of daimyō lords, but was embraced by government officials and business magnates. Figures like Inoue Kaoru, Masuda Dono, Nishikawa Nagao (the foundation of Tobu Railway), and Genyō Yūtsūji, who established Sankeien Garden in Yokohama, were instrumental in collecting valuable tea utensils that had become available after the decline of the shogunate. Many of these collected utensils were showcased in their personal museums, some of which are still accessible today.

Additionally, the practice of tea ceremony, once exclusively male, found its way into women’s education through schools for girls. In the Showa period, various regions witnessed the widespread hosting of tea ceremonies in temples and shrines, as well as large-scale tea gatherings, making tea ceremony more accessible to the general public. Despite the challenges faced during wartime and post-war periods, tea ceremony has continued to evolve and thrive, leading to its present state.

The history of tea ceremony is rich and multifaceted

This overview provides just a glimpse into its journey through time. By understanding this history, we gain a deeper appreciation for the significance of the